MLB’s power dynamics, Mbappé for president, and more

The Out in Left Weekly: June 23, 2024

MLB

Baseball’s TV business creates interesting power dynamics

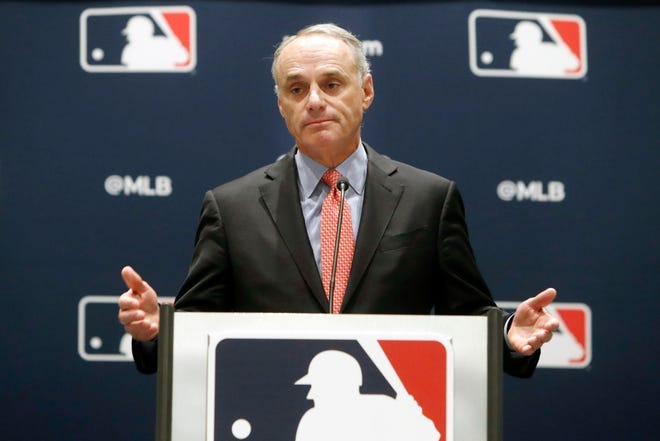

For once, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred is with the fans. As ESPN’s Alden Gonzalez reported this week, the league wants a bankruptcy judge to shut down Diamond Sports Group, the company that holds exclusive broadcasting rights for twelve MLB teams…