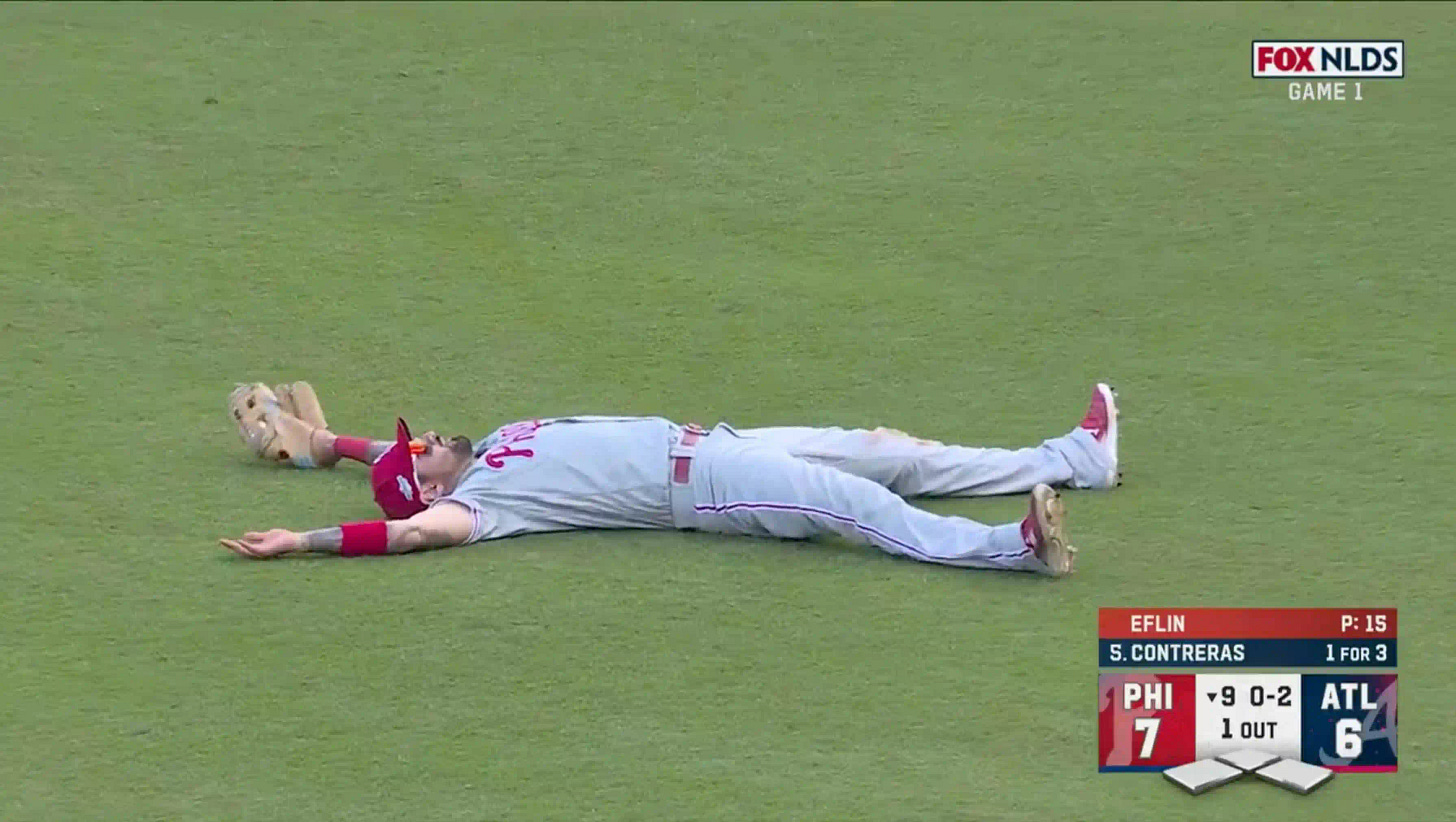

Nick Castellanos is all of us

Thoughts on the Phillies' most vulnerable and relatable player

For as good a baseball player as Phillies outfielder Nick Castellanos is, posterity will likely remember him for a derogatory comment he had nothing to do with.

“I made a comment earlier tonight that I guess went out over the air that I am deeply ashamed of,” Reds play-by-play man Thom Brennaman said…