The San Diego Padres could have been ours

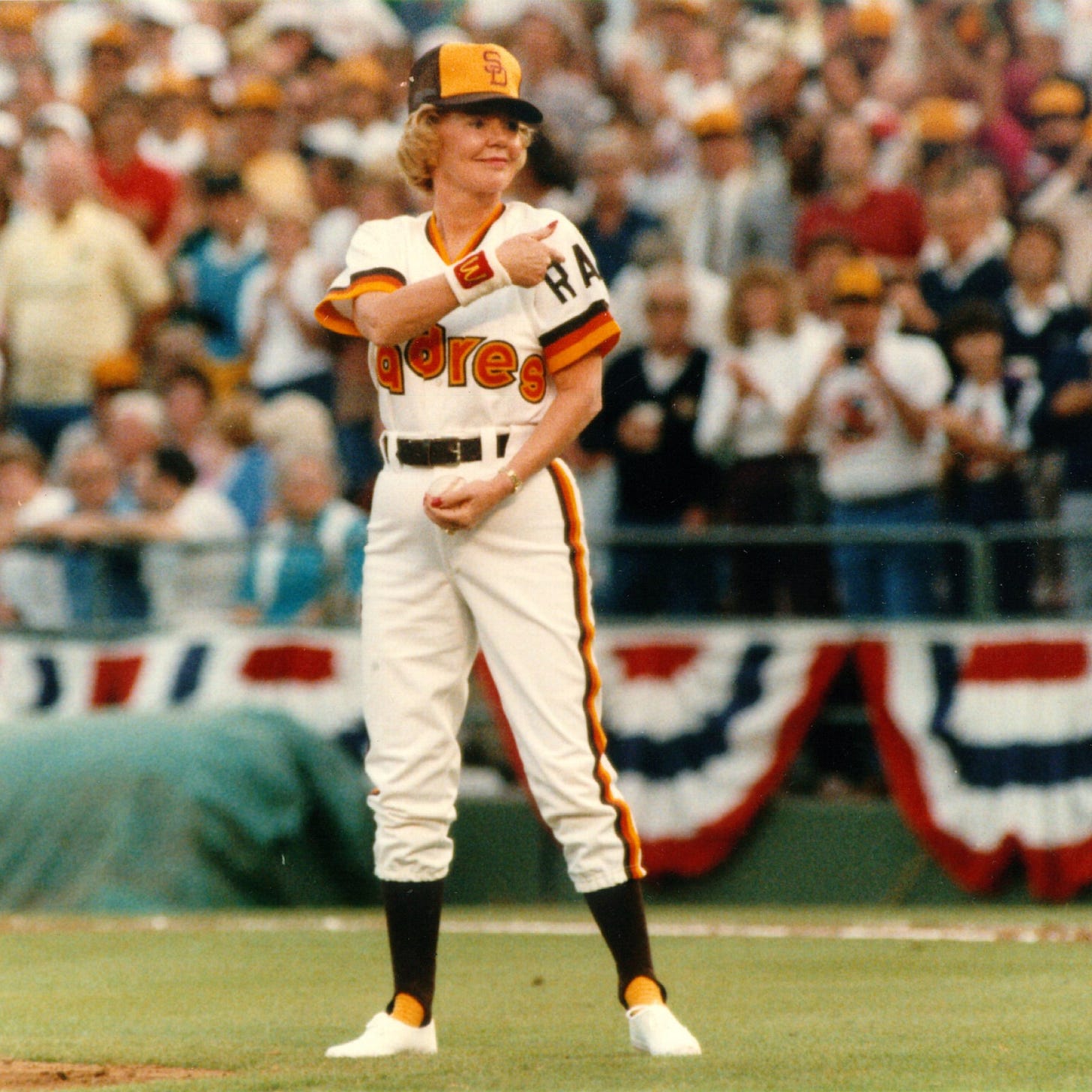

The Padres' owners are selling the team and are poised to make billions. It calls to mind Joan Kroc, who tried to give the team to the public.

The family that controls the San Diego Padres announced this week that they’re exploring a sale of the team. The Seidlers and their co-investors will make billions—billions that, except for the intervention of monopolists in 1990, could have existed in the public trust in perpetuity.

Ray Kro…