The US is sick and Oasis is the cure

TL;DR We need to care more

Oasis recently returned to a sold-out Wembley Stadium, sixteen years after bandleader Noel Gallagher imposed a hiatus, and at one point on the second night of the seven-show stand I noticed the Scottish lad in front of me splayed supine across the two rows in front of him, singing along, not missing a word, beer held aloft, not spilling a drop.

“Cast No Shadow,” a deep-cut ballad and one of the setlist’s piss-break songs, is what ignited this man. I lunged for and tugged at his arms, trying to right him, then he swung into my embrace, where he scream-sang the chorus into my left ear.

Bound with all the weight of all the words he tried to say

Chained to all the places that he never wished to stay

Bound with all the weight of all the words he tried to say

As he faced the sun he cast no shadow…

Oasis brings its triumphant reunion tour to the Americas this week. Toronto was first, then, at long last, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. The U.S. isn’t prepared.

That’s not because we’re afraid of rowdy Brits. We’ve handled them a couple times in our history, and we’re friends now. The Scot, with a smile so big it made his face look like a balled piece of paper, later handed me a white wine, served warm in a plastic cup, the one he forgot he ordered an hour previous.

It’s also not because the US doesn’t like Oasis, despite the Gallaghers’ mythologizing. They never did well with Americans, the brothers insist—the band’s social media accounts played into this throughout the tour cycle—but every reunion tour date is sold out and oversubscribed. For one of the New York shows, a friend resold tickets for two regular ass seats for over $2,000.

The US isn’t ready for Oasis because the band is going to remind the country how’ve we abandoned the business of caring.

The brief history of Oasis is this: Liam Gallagher had musical talent beaten into his head with a hammer and formed a band in 1991 with some friends, including one named Bonehead, who was presumably not beaten in the head with a hammer. Older brother Noel, then a pothead roadie for bands in their hometown Manchester, England, recognized something in and joined the outfit, becoming its primary songwriter.

By 1997, Oasis had released:

One of the best debut albums of all time (Definitely, Maybe)

One of the best-selling albums of all time (What’s the Story, Morning Glory?)

One of the most notoriously drug-fueled albums of all time (Be Here Now); and,

Some of the best B-sides in pop music history (“Acquiese” and “The Masterplan,” to name two).

Add in their 1996 Knebworth shows, at which they played to a quarter million people, and their coverage in the tabloids for fighting Blur, the paparazzi, and each other and Oasis was, by almost any metric, the biggest band in the world.

Then the 2000s hit them like a double-decker bus. In the summer of 2005, for example, 50 Cent dropped The Massacre, which will live on until the aliens invade thanks to “Candy Shop.” Oasis dropped Don’t Believe the Truth, which is already dead. The band hasn’t played one song from the album on the reunion tour.

Noel ended Oasis’ ignominy in 2009, just before a scheduled festival set in France, after he and Liam got into yet another fight. Guitars and plums served as projectiles. The brothers laid down their arms this year and, considering the reaction to the reunion tour, their band is probably more popular than ever.

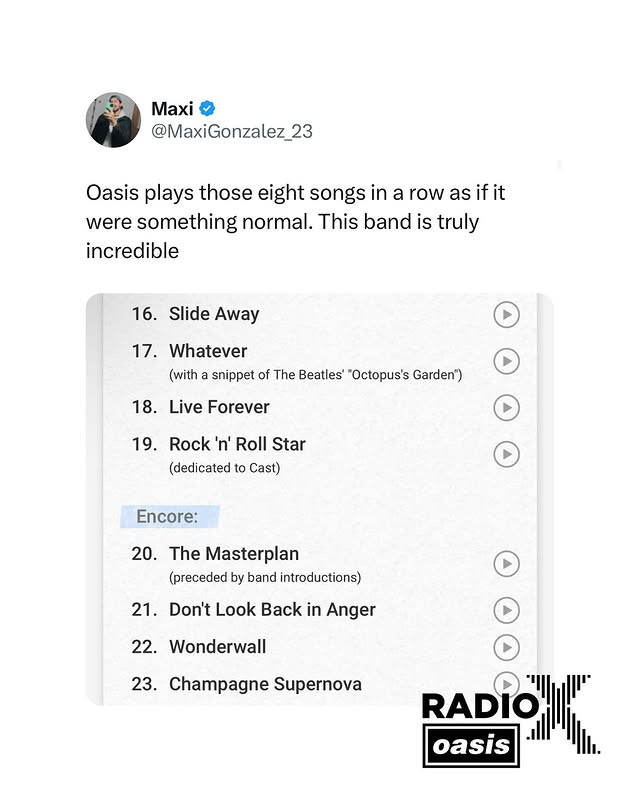

Oasis’ ten most popular songs have been streamed no fewer than 82 million times, and “Wonderwall” will eclipse 2.5 billion streams soon, thanks in large part to white people's weddings. One recent tweet, pinging around the Oasis-verse on social media, summed up the source of the band’s popularity:

But Oasis doesn’t endure because of quality. There were better, more creative musicians both from their hometown (The Smiths, The Stone Roses) and on Creation Records, their original label (Ride, My Bloody Valentine). And they don’t endure just because they said, incessantly, that they are the second coming of The Beatles.

Oasis was once and is again the biggest band in the world—and was once and is again a force with which America must reckon—because its music is universal, elemental, even, in a way that its peers are not.

“Noel Gallagher is not a great or even cogent lyricist, and his melodies can sometimes seem a little samey,” wrote music critic Steven Hyden in a review of the Wembley shows. “But when it comes to writing songs that large groups of individuals in various states of inebriation can sing in unison, perfectly, Bob Dylan and Beethoven have nothing on him… Oasis is constantly compared to the Beatles, the Sex Pistols, and the other iconic British rock bands. But their songs actually have more in common with ‘Happy Birthday’ or nursery rhymes.”

This sentiment is best represented by “Slide Away.”

Noel is a bullshitter. His story for how “Slide Away” came into the world, sometime in 1993, is that Johnny Marr of the Smiths “sent down” his signature guitars “to a load of scallys from a council estate in south Manchester,” as Noel described his band. Noel pulled a Les Paul from the case and started strumming, and, golly gee whiz, out spilled Oasis’ greatest song.

It’s as unlikely, or at least as fabricated, as the story of Noel writing “Supersonic” in 15 minutes in the studio while the rest of the band was out for Chinese food. There are no eye witnesses in either story.

This mythmaking is part of Oasis’ whole thing, and it reflects the Gallaghers’ massive egos, but it also serves a purpose. In public appearances, Bruce Springsteen talks about nothing besides his songs and his intimate relationship with them. He shares the inspiration, the meaning, the significance, how they’ve changed over the years. I love him, but it’s kind of deranged, and it has the effect of making them his songs. I think this plays into why there are few casual Bruce fans. A prerequisite to liking Bruce Springsteen is liking “Bruce Springsteen.” You must like the boxes into which he puts his music.

The Gallaghers are more interested in Oasis as public property. Noel making shit up about his songs protects them (and himself), in a way—the meaning and significance is created by the listener. This makes Oasis songs ours, allowing the band’s listenership to broaden outside the cult of personality. After all, what one person could own a nursery rhyme?

Noel’s songs speak for themselves, and not being wholly honest—that he wrote and rehearsed religiously, that “Slide Away” was about a soulmate, and that he probably worked on it for months before he got his hands on Marr’s guitar—the song gets to say anything it needs to.

In the opening chord exists yearning and vulnerability and knowing and sadness. The song’s core melody emerges, an acknowledgement that life goes on, that there is a hope, and the rhythm section kicks in, bringing us back to earth. In 13 seconds and without a word Noel creates a world.

Early recordings of “Slide Away” show it always had good bones, but it was at once thin and overstuffed. On one demo, the guitar overdubs are distracting and Liam’s vocal is detached from the music. The drumming is terrible. It sounds like three different songs being played at once.

The band re-recorded “Slide Away” as part of the Definitely Maybe sessions in late 1993, but the album didn’t satisfy anyone. They tried again in early 1994, only to produce yet another version that sounded nothing like the loud and urgent band they were on stage. So they dumped the jigsaw puzzle on sound engineer Owen Morris.

Morris removed the overdubs or buried them, and he treated Tony McCarroll’s drums like a photograph. He fixed them in post. Most importantly, Morris turned down Noel’s lead guitar, blasted Bonehead’s rhythm guitar, and compressed it all. He also clipped outros and faded songs out at their crescendos.

These are the techniques he used throughout Definitely Maybe, which result in its emotional heft and signature texture, it being almost as tactile as a chainsaw. This is most apparent and essential in “Slide Away,” which, before Morris, was cooked like a typical chicken breast, leathery on the edges and raw in the middle. By hewing closer to Oasis’ ethos on stage, Morris’s heavy hand turned it into a masterpiece. “Slide Away” possesses the feeling of love, of life. It’s what I felt at Wembley Stadium last month screaming along to the lyrics with 85,000 people.

The lyric makes this feeling explicit. Some lines are saccharine enough for a Disney song—for a nursery rhyme—but what makes “Slide Away” universal and enduring, besides the music and production, is its ambiguity and juxtaposition.

Slide away and give it all you got

My today fell in from the top

The narrator is instructing someone to get lost and be strong about it. But they are imploding over having to say that. This follows a pattern that’s common to many of Oasis’ best records. Any one line is logical, but in context it becomes almost nonsense, or at least conflicting. It allows the listener to “see” into the music whatever they want.

I dream of you and all the things you say

I wonder where you are now

The narrator talks presently with their love interest, then pivots to separation and sentimentality. Is “Slide Away” a love song or a breakup song? Yes.

Hold me down, all the world's asleep

Need you now, you've knocked me off my feet

More instructing and expressing in the present, as if they came back, but then it’s right back to implying separation. Does the present tense of the lyric keep the song fresh and immediate or does it make it confusing and ambiguous? Yes.

I dream of you and we talk of growing old

But you said, "Please don't"

The narrator starts the song telling their lover to leave, but now they’re desperate for them and reveals a tender, intimate moment between the two. But is the narrator even talking to someone or just to themselves? Yes.

Critics of Oasis dock points for the band’s overplayed and seemingly unchallenging radio hits and for their laddish, insouciant behavior. “I have 87 million pounds in the bank. I have a Rolls Royce. I’ve got three stalkers. I’m about to go onto the board at Manchester City. I’m part of the greatest band in the world. Am I happy with that?” Noel said during Oasis’ peak. “No, I’m not! I want more!”

But look under the hood and it’s clear that Noel is craftier than Hyden gives him credit for. The riffs and melodies cling to the ear, but it’s the sensitivity and wisdom that are the foundation of Oasis world-conquering machine. All of life can be summed up by two contrasting lines in the chorus:

Let me be the one who shines with you

In the morning, we don't know what to do

We confess and express our affection, and we have good times with someone, or with many people, but then do we actually know what we’re doing? Is the hollowness in the morning a side effect of a necessary drug or a symptom of a disease? Is that even hollowness, or is it a latent fulfillment? We aspire to shine with others. Do we ever get to do that, or is the chase enough, or is a dull sheen enough? Not many pop songs pose these questions, not in the way “Slide Away” does, and not at a 85,000-person stadium show, and who’s doing the asking is Noel’s little brother Liam.

Liam’s vocal on “Slide Away” shows why he is one of the best singers and frontmen of the last 35 years. It is at once desperate and secure, admiring and lamenting. It’s technically brilliant. The notes he hits in the chorus are why he sounded like a hoarse Kermit the Frog through the 2000s, but it was worth it to fly too close to the sun.

The way he started the second chorus at Knebworth might be the single greatest moment for the band and in turn one of the greatest moments in pop music history. (Study Oasis enough and you, too, will start making grand statements that are impossible to either verify or refute.) “There's a point in ‘Slide Away’ where [Liam] almost shouts, ‘Now that you're mine.’ He sings it with such passion. It was incredible,” recalled a fan in the Knebworth 1996 documentary.

It reflects Liam’s willingness to take Noel’s songs at face value, as Noel wants them to be received, as well as his innate understanding of what his brother is trying to achieve. In this way, Liam is as an actor as much as he’s a singer. He throws himself into a role and never pushes back against the direction. The music and the lyric of “Slide Away” call for Liam to elicit the feeling of both pushing away a lover and holding onto them. It requires him to be both innocent and shrewd. It requires him to be everything all at once.

Oasis has bigger, more famous songs, of course, but it’s telling that there aren’t any notable covers of “Slide Away.” No band today can bring the necessary weight to a recording because it’s not the 90s in Owen Morris’s studio. You can strip it down, as Noel has done on some nice live versions, but they miss something. And no one’s touching Liam’s vocal. I think artists stay away from it because it is perfect and it encapsulates everything, and that’s because Liam and Noel are earnest.

The US didn’t reject this.

Definitely, Maybe came out in August 1994, yet Oasis first played the States a month before that, and until Los Angeles takes its place next week the bustling metropolis of Fairfax, Virginia, is the last American city to host the Gallaghers, in December 2008.

Americans also bought millions of copies of Morning Glory. Oasis played Letterman when that was A Thing. Be Here Now charted at number two, something Bruce Springsteen didn’t achieve until The River, his fifth album, that hack. And the response to the reunion tour has been rapturous.

It’s the most American thing ever, though, to boil something down to its commercial success.

As James Hargreaves documents on his YouTube channel, Liam flipped off an attendee at Oasis’ first American show before the first song had ended. Liam later expressed his frustration with their American audience:

“They want to be told how great they are—‘Are you having a great time? Clap your hands together!’ I’m not into any of that nonsense. I never felt the pressure to move or to get a little dance routine together or speak to the crowd or even acknowledge the crowd. Are they here to hear us talk about our day? It’s not a comedy show and we are not there for a laugh. We are up there to sing and play music.”

Liam the Philosopher continued: “I ain’t saying fuck all. They were confused when there wasn’t chatting or banter in between the songs. It would just go silent. Sometimes people get awkward around silences, where I thrive on it.”

This calls to mind televised American sports, in which the commentators never shut the fuck up; and in-person American sports, at which there are noises and music played during every stoppage; and American television, whose commercials are louder and more annoying than the shows; and American street life, which barely exists and is ruined by backfiring Honda Civics and growling Ram 1500s and blaring Bluetooth speakers.

For his part, Noel chided that initial audience by asking, “Where abouts in Liverpool are you from?” Zinger!

After Wembley, Steven Hyden claimed, “Oasis has the most decisive home-field advantage I have ever witnessed in music,” so in 1994 the brothers could have just been frustrated by not playing to the proud, rabid, and growing audience in their native England. Or they could have plainly not liked the US, and the audience (and the media, promoters, and executives) responded in kind. In this case, the US not taking to Oasis was a self-fulfilling prophecy, one that the Gallaghers are now literally capitalizing on.

It’s the second-most American thing ever, though, to think we’re not the problem, and when the Gallaghers put their fingers in the wound we reacted predictably: We gazed skeptically upon the newcomers and ultimately rejected them socially, if not economically.

We are an insecure people, and that insecurity breeds self-referentiality, irony, and cynicism. Bands banter with American audiences to lift us from this state, and it’s a necessary and not altruistic act. Artists wouldn’t get any energy or response from an audience that views the show through a phone and descends into self-consciousness about whether they’re having a good time, or whether the obscene ticket price was worth it, or why the music doesn’t sound as good recorded, or why the tall, smelly kid in front of me won’t just move. These are contemplations that prevent us from, say, losing our mind over “Cast No Shadow” and trying to crowd surface in seated section 142. It also prevents us from being understanding when someone crashes into us, as the people in the area were.

Cultural expressions of our self-referentiality and cynicism are so common as to seem the natural order of things. Is it even a commercial if there isn’t a character breaking the fourth wall and/or acknowledging that they’re selling something?

Seinfeld ironically presents the trials and tribulations of an aspiring comic and that comic is played by an ironic, aspiring comic named Seinfeld. That show has been running on one channel or another for four decades now.

Then there’s the apotheosis of our psyche, Deadpool. If you want to know about the US, then put on that braindead franchise.

When Oasis first arrived stateside, Seinfeld was in the middle of its run and about to debut its sixth season, the first to top the TV charts. It’s little wonder why Noel found a country where “they just blankly look at you.” The band presented their music and personas earnestly and they were sincere—sincere about their ambition and fears and brashness and disdain, but sincere nonetheless.

It’s as if those sentiments have been marinating in England for the past 16 years, and at Wembley they contributed to the most positive and euphoric live event I’ve ever experienced, something noticed by Slate’s Scaachi Koul. “They”—us men—“made friends with strangers seated next to them, offered vape hits, politely shuffled by to get a drink after the opening act,” she wrote, and during Oasis’ set “thousands upon thousands of white guys singing ‘HER SOUL SLIDES AWAY’ was a comfort and a unity in just bein’ blokes.”

It’s fitting that Koul compared Oasis to Taylor Swift—“This was the ‘Eras’ tour for men whose fathers punched them on the arm on their wedding day.”—since I believe Swift’s massive fan base and the obsessive criticism she receives is due in part to her earnestness. Find me better songs in her catalog than “Love Story” or “All Too Well,” two sentimental pop music masterpieces that aren’t that dissimilar to “Slide Away.” You cannot. Another reason why she receives such blowback is because she’s a woman.

Like Koul, I don’t pretend to think Oasis is going to end the “male loneliness crisis.” Women aren’t going to be treated better because of a concert, though I wish that could be true. And no matter what the band says or does, Americans will absolutely still drive pickup trucks to get fast food and watch the NFL on TV and think its a good product.

I do know that fulfillment elicited by cynicism is temporary, if not illusory. The real thing is found in each other, as painful and annoying as it is for this introvert to admit. My best relationships, the relationships from which I receive the most, are the ones in which I am vulnerable and in which I give the most. My favorite moments in life are not when I was sarcastic, guarded, or skeptical.

I went to Wembley with my friend Miles. We both teared up during “Half the World Away.” During “Don’t Look Back in Anger,” I put my arm around his shoulder and, yes, we sung “HER SOUL SLIDES AWAY.” By flying to London to see Oasis we fled the land where caring is a crime. For a few nights, Oasis gives the US another opportunity to realize that.

So so good! Great point about Springsteen in here (and I love the man.) And the un-selfconciousness of men singing together in public feels European, even LatAm in some contexts, and absolutely Not American, we're not allowed, we're Seinfeld. Thanks for this!

Beautiful piece and so true this line

“ “But when it comes to writing songs that large groups of individuals in various states of inebriation can sing in unison, perfectly, Bob Dylan and Beethoven have nothing on him… “

Please take a look at mine on Oasis 🙏🏻

https://substack.com/@collapseofthewavefunction/note/p-170698440?r=5tpv59&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action